| Admissions | Accreditation | Booksellers | Catalog | Colleges | Contact Us | Continents/States/Districts | Contracts | Examinations | Forms | Grants | Hostels | Honorary Doctorate degree | Instructors | Lecture | Librarians | Membership | Professional Examinations | Programs | Recommendations | Research Grants | Researchers | Students login | Schools | Search | Seminar | Study Center/Centre | Thesis | Universities | Work counseling |

Cardiology Emergencies

| Pediatric Cardiology Emergencies | |||||||||||

| Cardiac Emergencies - Adult | |||||||||||

|

* Cardiopulmonary Arrest * Hypertensive Emergency * Aortic Dissection * Acute Pulmonary Edema | |||||||||||

| Questions | |||||||||||

|

Acute Ischemic Coronary Syndrome (AICS)

Low Risk Chest Pain Congestive Heart Failure Dysrhythmias Implantable Devices Intravascular Clotting: DVT and PTE Shock and Resuscitation Catastrophic Cardiovascular Conditions Stroke and TIA Resuscitation | |||||||||||

|

What are cardiology medical emergencies? How should you do a quick assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of a person reported as a cardiology medical emergency? | |||||||||||

| Patient Intake Form | |||||||||||

| Cardiology | |||||||||||

| * Cardiopulmonary Arrest | |||||||||||

|

* Hypertensive Emergency * Aortic Dissection * Acute Pulmonary Edema | |||||||||||

| Questions | |||||||||||

|

Acute Ischemic Coronary Syndrome (AICS)

Low Risk Chest Pain Congestive Heart Failure Dysrhythmias Implantable Devices Intravascular Clotting: DVT and PTE Shock and Resuscitation Catastrophic Cardiovascular Conditions Stroke and TIA Resuscitation | |||||||||||

|

* Cardiopulmonary Arrest * Hypertensive Emergency * Aortic Dissection * Acute Pulmonary Edema Cardiovascular emergencies are life-threatening disorders that must be diagnosed quickly to avoid delay in treatment and to minimize morbidity and mortality. Patients may present with severe hypertension, chest pain, dysrhythmia, or cardiopulmonary arrest. In this chapter, we will review the clinician's approach to these disorders and their treatments and provide links to other informative resources. Acute coronary syndromes are covered elsewhere in this text. Cardiopulmonary arrest Causes Cardiopulmonary arrest occurs as a result of a multitude of cardiovascular, metabolic, infectious, neurologic, inflammatory, and traumatic diseases. However, the clinician must be aware of several specific causes, including drug toxicity or overdose, myocardial ischemia or infarction, hyperkalemia, torsades de pointes, cardiac tamponade, and tension pneumothorax. The marked differences in therapeutic intervention among these various causes underscore the need for accurate recognition. The end point of these disorders is commonly pulseless ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, pulseless electrical activity, symptomatic bradycardia, or asystole. Prevalence An estimated 250,000 people per year in the United States experience sudden cardiac death. However, national statistics on the actual prevalence of cardiopulmonary arrest are unreliable because no single agency collects data relating to the number of patients who receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) annually. Ischemic cardiovascular disease underlies many cardiopulmonary arrests in adults. The value of early CPR and immediate defibrillation has been proven in many community-based studies. 1–4 Additionally, among adults, in whom ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, or both is more common, the increased use of automated external defibrillators (AEDs) by emergency medical services (EMS), businesses, and airports has improved survival. 5–8 Without defibrillation, mortality from ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, or both increases by approximately 10% per minute. 9–12 Diagnosis and Therapy The American Heart Association, in collaboration with the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation, has established guidelines for resuscitation of cardiac arrest patients. 13,14 In each resuscitation scenario, four concepts should always apply: 1. Activate EMS or the designated code team. 2. Perform basic life support (CPR). 3. Evaluate heart rhythm and perform early defibrillation as indicated. 4. Deliver advanced life support (e.g., intubation, intravenous [IV] access, transfer to a medical center or intensive care unit). Ventricular Tachycardia or Ventricular Fibrillation 1. Conduct a primary ABCD survey (airway, breathing, circulation, differential diagnosis). Place airway device as soon as possible. Confirm placement, secure device, and confirm oxygenation and ventilation. Establish IV access, identify rhythm, and administer drugs appropriate for rhythm and condition. Search for and treat identified reversible causes, with focus on basic CPR and early defibrillation. 2. On arrival to an unwitnessed cardiac arrest or downtime longer than 4 minutes, five cycles (approximately 2 minutes) of CPR are to be initiated before evaluation of rhythm. If the cardiac arrest is witnessed or downtime is shorter than 4 minutes, one shock may be administered immediately if the patient is in ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (see below). 3. If the patient is in ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia, shock the patient once using 200 J on biphasic (or equivalent monophasic, 360 J). 4. Resume CPR immediately after attempted defibrillation, beginning with chest compressions. Rescuers should not interrupt chest compression to check circulation (e.g., evaluate rhythm or pulse) until five cycles or 2 minutes of CPR have been completed. 5. If there is persistent or recurrent ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation despite several shocks and cycles of CPR, perform a secondary ABCD survey with a focus on more advanced assessments and pharmacologic therapy. Pharmacologic therapy should include epinephrine (1-mg IV push, repeated every 3 to 5 minutes) or vasopressin (a single dose of 40 U IV, one time only). 6. Consider using antiarrhythmics for persistent or recurrent pulseless ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation. These include amiodarone, lidocaine, magnesium (if there is a known hypomagnesemic state), and procainamide (class indeterminate for persistent and Class IIb for recurrent). 7. Resume CPR and attempts to defibrillate. Pulseless Electrical Activity 1. Assess the patient and conduct a primary ABCD survey. 2. Review for the most frequent causes of pulseless electrical activity, the five Hs and five Ts: hypovolemia, hypoxia, hydrogen ion (acidosis), hyperkalemia (or hypokalemia), and hypothermia and tablets (drug overdose, accidents), tamponade (cardiac), tension pneumothorax, thrombosis (coronary), and thrombosis (pulmonary embolism). 3. Administer epinephrine (1-mg IV push repeated every 3 to 5 minutes) or atropine (1 mg IV if the heart rate is slow, repeated every 3 to 5 minutes as needed, to a total dose of 0.04 mg/kg). 4. Conduct a secondary ABCD survey. Bradycardia 1. Determine whether the bradycardia is slow (heart rate less than 60 beats/min) or relatively slow (heart rate less than expected relative to underlying condition or cause). 2. Conduct a primary ABCD survey. 3. Check for serious signs or symptoms caused by the bradycardia. 4. If no serious signs or symptoms are present, evaluate for a type II second-degree atrioventricular block or third-degree atrioventricular block. 5. If neither of these types of heart block is present, observe. 6. If one of these types of heart block is present, prepare for transvenous pacing. If symptoms develop, use a transcutaneous pacemaker until the transvenous pacer is placed. 7. If serious signs or symptoms are present, begin the following intervention sequence: 1. Atropine, 0.5 up to a total of 3 mg IV 2. Transcutaneous pacing, if available 3. Dopamine, 5 to 20 mcg/kg/min 4. Epinephrine, 2 to 10 mcg/min 5. Isoproterenol, 2 to 10 mcg/min 8. Conduct a secondary ABCD survey. Asystole 1. Conduct a primary ABCD survey. 2. Perform transcutaneous pacing immediately if needed. Consider transvenous pacing if transcutaneous pacing fails to capture. 3. Administer epinephrine (1-mg IV push, repeated every 3 to 5 minutes) or atropine (1 mg IV repeated every 3 to 5 minutes, up to a total of 3 mg). 4. Conduct a secondary ABCD survey. 5. If asystole persists, consider withholding or ceasing resuscitative efforts. Hypertensive emergency Definition A hypertensive emergency is an acute, severe elevation in blood pressure accompanied by end-organ compromise. In newly hypertensive patients, a hypertensive emergency is usually associated with a diastolic blood pressure higher than 120 mm Hg. Nephrosclerosis that causes acute renal failure frequently complicates hypertensive emergencies, with resultant hematuria and proteinuria. Nephrosclerosis also may perpetuate the elevation of systemic pressure through ischemic activation of the renin-angiotensin system. Ocular involvement with retinal exudates, hemorrhages, or papilledema connotes a worse prognosis. 15,16 Complications of particular concern include hypertensive encephalopathy, aortic dissection, and eclampsia. Hypertensive encephalopathy signals the presence of cerebral edema and loss of vascular integrity. If left untreated, hypertensive encephalopathy may progress to seizure and coma. 17,18 Aortic dissection is associated with severe elevations in systemic blood pressure and wall stress, requiring immediate lowering of the blood pressure and emergent surgery to reduce morbidity and mortality. Eclampsia, the second most common cause of maternal death, occurs from the second trimester to the peripartum period. It is characterized by the presence of seizures, coma, or both, in the setting of preeclampsia. Delivery remains its only cure. 19 Causes Hypertensive emergencies result from an exacerbation of essential hypertension or have a secondary cause, including renal, vascular, pregnancy-related, pharmacologic, endocrine, neurologic, and autoimmune causes (Box 1). Box 1: Causes of Hypertensive Emergencies Essential hypertension Renal causes Renal artery stenosis Glomerulonephritis Vascular causes Vasculitis Hemolytic-uremic syndrome Thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura Pregnancy-related causes Preeclampsia Eclampsia Pharmacologic causes Sympathomimetics Clonidine withdrawal, beta blocker withdrawal Cocaine Amphetamines Endocrine causes Cushing's syndrome Conn's syndrome Pheochromocytoma Renin-secreting adenomas Thyrotoxicosis Neurologic causes Central nervous system trauma Intracranial mass Autoimmune cause Scleroderma renal crisis Prevalence The prevalence of hypertension rises substantially with increasing age in the United States and is greater among blacks than among whites in every age group. 20,21 Based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), the prevalence of hypertension in those older than 70 years was found to be approximately 55% to 60% of the U.S. population. 22,23 A British study has revealed that fewer than 1% of patients with primary hypertension progress to hypertensive crisis. 24 This study also showed that, despite increasingly widespread therapy, the number of patients presenting with hypertensive crises did not decline between 1970 and 1993. Pathophysiology Any syndrome that produces an acute rise in blood pressure may lead to a hypertensive crisis. Cerebral vasomotor autoregulation is a key facet of a patient's symptomatic presentation. Patients without chronic hypertension will develop hypertensive crisis at a lower blood pressure than those with chronic hypertension. Although not completely understood, an initial rise in vascular resistance mediated by vasoconstrictors such as angiotensin II, acetylcholine, or norepinephrine is responsible for the acute increase in blood pressure. This cascade exceeds the vasodilatory response of the endothelium, mediated primarily by nitric oxide. Mechanical destruction of the endothelium by shear stress leads to further vascular obstruction, platelet aggregation, inflammation, and subsequent blood pressure elevation. The rate at which this occurs determines the rate of increase in systemic vascular resistance as well as the acuity of a patient's presentation. Clinical Evaluation The symptoms and signs of a hypertensive emergency vary widely. Symptoms of end-organ involvement include headache, blurry vision, confusion, chest pain, shortness of breath, back pain (e.g., aortic dissection) and, if severe, seizures and altered consciousness. 15,16 Physical examination should assess end-organ involvement, including detailed fundoscopic, neurologic, and cardiovascular examinations, with emphasis on the presence of congestive heart failure and bilateral upper extremity blood pressure measurements. Laboratory evaluation should include measurement of the complete blood count with differential and smear evaluations, measurements of electrolyte, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine levels, and electrocardiography, chest radiography, and urinalysis. Treatment No large randomized clinical trials have assessed therapy in hypertensive emergency; therapeutic intervention is largely a result of expert opinion. All patients with end-organ involvement should be admitted for intensive monitoring and have an arterial blood pressure line placed. 16 Pharmacologic Therapy IV vasodilator therapy to achieve a decrease in mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 20% to 25% or a decrease in diastolic blood pressure (DBP) to 100 to 110 mm Hg in the first 2 hours is recommended. Decreasing the MAP and DBP further should be done more slowly because of the risk of decreasing perfusion of end-organs. 16 Several drugs have proven beneficial in achieving this goal ( Table 1 ). Table 1: Intravenous Vasodilator Therapy for Hypertensive Crisis Drug Dosage Half-Life Nitroprusside 2.5-10 mcg/kg/min 1-2 min Labetalol 20- to 80-mg bolus, 2 mg/min maintenance 2-6 hr Fenoldopam * 0.1-0.5 mcg/kg/min 10-20 min Enalaprilat † 1.25- to 5-mg bolus 4-6 hr * Recommended starting dose is 0.1 mcg/kg/min, with a slow increase to a maximum rate of 0.5 mcg/kg/min and/or target blood pressure. †Use specifically for angiotensin-converting enzyme–mediated hypertensive crises, such as scleroderma renal crisis. It is contraindicated in pregnancy. Medical Economics Staff, Physician's Desk Reference, 57th Edition, 2003. At our institution, we focus on reducing shear forces and combine a beta blocker with sodium nitroprusside (SNP). In cases of marked catecholamine level elevation, large doses of IV beta blockers may be required to achieve blood pressure reduction. One exception to the use of large doses of beta blockers is cocaine overdose, for which vasodilators and benzodiazepines are the mainstays of therapy. Additional Considerations 1. In addition to reducing MAP and DBP with medications as described above, early surgical intervention for type A dissection has proved to reduce morbidity and mortality. Reduction in shear stress is best achieved with IV beta blockade and SNP. 25,26 2. In addition to delivery, IV magnesium, hydralazine (pregnancy class B drug), and labetalol (pregnancy class B drug) have value in the treatment of preeclampsia and prevention of eclampsia. 19 Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors are strictly contraindicated because of adverse effects to the fetus, although this occurs in the first trimester. 3. Antihypertensive therapy remains controversial in the presence of stroke because a high cerebral perfusion pressure may be neurologically beneficial. Prompt neurologic consultation should be obtained. Aortic dissection Definition Aortic dissection. The tear has penetrated the diseased media (A), with resultant rupture and hemorrhage (B). Figure 1: Click to Enlarge Aortic dissection is a tear of the aortic intima that allows the shear forces of blood flow to dissect the intima from the media and, in some cases, penetrate the diseased media with resultant rupture and hemorrhage (Fig. 1). 27 Sixty-five percent of dissections originate in the ascending aorta, 20% in the descending aorta, 10% in the aortic arch, and the remainder in the abdominal aorta. 28,29 By the Stanford system, a dissection that involves the ascending aorta is classified as type A, and one that does not is classified as type B (Fig. 2). Dissections are further classified by chronicity as acute (shorter than 2 weeks) or chronic (longer than 2 weeks); mortality peaks at 2 weeks at approximately 80% and then levels off. 28 Aortic dissection, types A and B. Type B aortic dissection does not involve the ascending aorta. Figure 2: Click to Enlarge Causes Any disease that weakens the aortic media predisposes patients to dissection. These include aging, hypertension, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, bicuspid aortic valve (associated with medial degeneration), coarctation, and Turner's syndrome. Pregnancy poses a unique risk to women with any of these diseases because of increased blood volume, cardiac output, and shear forces on the aorta. Of dissections in women younger than 40 years, 50% occur in the peripartum period. 30 Trauma from catheters or intra-aortic balloon pumps may also dissect the aortic intima. 31 Aortic dissection is infrequently associated with blunt trauma. Clinical Presentation Most patients present with acute chest pain that is often tearing or ripping in nature, which peaks in intensity at its onset. Uncommonly, patients may present with congestive heart failure (from accompanying acute aortic insufficiency, tamponade, or both), cerebrovascular accident (involvement of the carotid artery or vertebrobasilar system), syncope (tamponade), or cardiac arrest. 32,33 On physical examination, hypertension is usually present, either as the primary cause of dissection or secondary to renal artery involvement. Acute aortic insufficiency with a resultant diastolic murmur may complicate ascending dissections. Loss of pulse, decrease in blood pressure, or both, often asymmetrically, are also found in the many patients. 32 Dissection of the spinal arteries, although rare, may produce secondary paraplegia. Chest radiographs may reveal an abnormality in approximately 70% to 80% of patients, such as a widened mediastinum or loss of the demarcation of the aortic knob, pleural effusion, or pulmonary edema. 32 Importantly, a normal chest radiograph is not incompatible with an aortic dissection. The electrocardiogram (ECG) may reveal left ventricular hypertrophy, ST depression, T wave inversion, or ST elevation. Electrocardiographic changes indicating inferior territory injury may herald right coronary ostial involvement in 1% to 2% of aortic dissection cases. Diagnosis Recognition of several signs is essential in the imaging of aortic dissection because they affect treatment and outcome: 1. Involvement of the ascending aorta 2. Location of dissection flap, intimal tear 3. Presence of pericardial fluid, cardiac tamponade 4. Involvement of coronary ostia Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a sensitivity and specificity of approximately 98% for detection of dissection. Transesophageal echocardiography has a sensitivity of approximately 98%; however, its lower specificity, 77% to 97%, reflects differences in operator experience. 29,35 Computed tomography sensitivity for detection of dissection is approximately 83% to 94%, whereas its specificity ranges from 87% to 100%, depending on the study. 34,35 Choice of testing should be based on the medical center's expertise, hemodynamic stability of the patient, and access to the imaging modality. 34–36 Although MRI remains the gold standard, its lack of portability, limited access, and long duration of imaging make this a less favorable option in the care of acute aortic dissection in some centers. 36 Treatment Surgery Surgical therapy is the best option for an acute aortic dissection involving the ascending aorta. Studies have shown that delaying surgical intervention, even to carry out left heart catheterization, aortography, or both, results in worse outcomes. 37–39 Surgical repair in patients with type B dissection is generally reserved for those with end-organ compromise or those who do not respond to medical therapy. Medical Therapy Medical therapy should be initiated in all patients with acute dissection. Reductions of shear force and blood pressure should be the primary goals. Beta blockers should be given parenterally and titrated to effect (generally, pulse 50 to 60 beats/min). In our institution, we then add SNP because of its rapid onset and ease of titration, aiming for a MAP of 65 to 75 mm Hg. In the hypotensive patient, pericardial tamponade, aortic rupture, myocardial infarction, or a combination of these should be suspected. Volume replacement and early surgical intervention should be pursued. Pericardiocentesis should be avoided if tamponade is present, because immediate surgical intervention is the therapy of choice. If hypotension persists, norepinephrine and phenylephrine are the vasopressors of choice because of their limited effects on shear force. Endovascular stenting, a rapidly growing field, remains investigational in this setting. Acute pulmonary edema Definition Acute pulmonary edema is an emergency that necessitates admission to the hospital. It has two major forms, cardiogenic and noncardiogenic. We will focus on cardiogenic pulmonary edema, which generally is more reversible than the noncardiogenic form. Cardiogenic pulmonary edema results from an absolute in-crease in left atrial pressure, with resultant increases in pulmonary venous and capillary pressures. In the setting of normal capillary permeability, this increased pressure causes extravasation of fluid into the alveoli and overwhelms the ability of the pulmonary lymphatics to drain the fluid, thus impairing gas exchange in the lung. 40,41 Causes and Pathophysiology Left ventricular systolic dysfunction, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, and obstruction of the left atrial outflow tract are the primary causes of increased left atrial pressure. Left ventricular systolic dysfunction is the most common cause of cardiogenic pulmonary edema. 40 This dysfunction can be the result of coronary artery disease, hypertension, valvular heart disease, cardiomyopathy, toxins, endocrinologic or metabolic causes, or infections. Diastolic dysfunction results in impaired left ventricular filling and elevation in left ventricular end-diastolic pressure. In addition to myocardial ischemia, left ventricular hypertrophy, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, and infiltrative or restrictive cardiomyopathy are all causes of diastolic dysfunction. Left atrial outflow obstruction is often a result of valvulopathy, such as mitral stenosis or mitral regurgitation, but also can be caused by tumors (atrial myxoma), dysfunctional prosthetic valves, thrombus, and cor triatriatum. It is imperative to distinguish between mitral regurgitation and mitral stenosis, given their very different treatments. Diagnosis Pulmonary edema is diagnosed by the presence of various signs and symptoms, including tachypnea, tachycardia, crackles (reflecting alveolar edema), hypoxia (secondary to alveolar edema), and S3 or S4 heart sounds, or both. Additionally, if hypertension is present, it may represent diastolic dysfunction, decreased left ventricular compliance, decreased cardiac output, and increased systemic vascular resistance. The presence of increased jugular venous pressure indicates increased right ventricular filling pressure secondary to right ventricular or left ventricular dysfunction. Finally, the presence of peripheral edema indicates a certain chronicity to the patient's condition. Laboratory data associated with pulmonary edema include hypoxemia on arterial sampling and a chest radiograph showing bilateral perihilar edema and cephalization of pulmonary vascular marking. Cardiomegaly, pleural effusion, or both may be present. Two-dimensional echocardiography may be helpful in the acute setting to assess left ventricular and right ventricular size and function and to look for valvular stenosis or regurgitation and pericardial pathology. The electrocardiogram (ECG) may reflect ongoing ischemia, injury, tachycardia, and atrial or ventricular hypertrophy. Treatment Mainstays of immediate therapy include improving oxygen delivery to end organs, decreasing myocardial oxygen consumption, increasing venous capacitance, decreasing preload and afterload, with careful attention to MAP, and avoiding hemodynamic embarrassment. All patients should receive supplemental oxygen to maximize oxygen saturation of hemoglobin. Administration of continuous positive airway pressure provides positive airway pressure, increases gas exchange, and perhaps decreases preload via decreased intrathoracic pressure. 42,43 Endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation should be used immediately if noninvasive supplemental oxygenation proves inadequate. In our experience, repeated attempts to improve oxygenation with noninvasive positive pressure ventilation often prove futile, and restoration of oxygenation is best achieved via endotracheal intubation. Pharmacologic Therapy The pharmacologic agents most commonly used in the treatment of acute pulmonary edema are nitroglycerin, SNP, nesiritide, and diuretics. 44 Nitroglycerin acts immediately to decrease preload and afterload. 45 It should be used for the management of patients with pulmonary edema who are not in cardiogenic shock. Sublingual administration allows rapid delivery of a large dose, which is often required to decrease preload. Parenteral administration also should be used in the nonhypotensive patient and, based on symptoms, titrated to a MAP of approximately 70 to 75 mm Hg. SNP is an effective vasodilator that is often required for the treatment of the hypertensive patient with pulmonary edema. 46 Its use requires arterial blood pressure monitoring. SNP should be used with caution in the setting of liver dysfunction, although thiocyanate toxicity is uncommon and usually occurs after prolonged infusion at high doses. Concomitant use of nitroglycerin should be strongly considered in the ischemic patient. A recent addition to the pharmacologic armamentarium, nesiritide is a vasodilator that acts by increasing the level of cyclic guanosine monophosphate, which, in turn, causes smooth muscle cell relaxation. In one trial, it proved superior to low-dose IV nitroglycerin. 47,48 Its serum half-life and blood pressure–lowering effect are much longer than SNP; therefore, it should be used with caution in a patient with a low or low-normal MAP. However, the use of the drug does not require invasive hemodynamic monitoring. Intravenous diuretics are most helpful for the treatment of volume overload in chronic congestive heart failure. Their vasodilatory and diuretic properties also are useful in the management of pulmonary edema. Diuretics should be used with caution in the euvolemic patient to avoid compromising cardiac output and oxygen delivery. Summary * Cardiopulmonary arrest has several causes, all of which require prompt resuscitative efforts. * Hypertensive emergency warrants admission for intensive monitoring and arterial blood pressure line placement. * Aortic dissection categorized as type A requires emergent surgery, whereas type B is managed medically. * Acute pulmonary edema should be treated by improving oxygen delivery to end organs, decreasing myocardial oxygen consumption, increasing venous capacitance, and decreasing preload and afterload. | |||||||||||

Basic Life Support|

What is CPR? |

10 CPR KNOWLEDGE QUESTIONS

|

How often should I stop CPR to check for signs of life?

| What about compression-only CPR? How much of the heart's pumping does CPR really simulate? I'm worried that I might further injure someone by moving them after an accident. What should I do? Why don't you cover 2-person CPR on your site? How much good can it really do to breathe carbon dioxide into someone's lungs out of yours? How do you know if the CPR you're doing is working?

Initial Assessment: | Child: 1. How far do you tilt the child’s head to open the airway? Infant: 1. How do you check an infant for consciousness? 2. How far do you tilt an infant’s head to open the airway? 3. How do you check an infant’s pulse? Adult: 1. When using a BVM, how often should you give rescue breaths? Child: 1. How far do you tilt the child’s head to open the airway? 2. When using a BVM, how often should you give rescue breaths? Infant: 1. How far do you tilt an infant’s head to open the airway? 2. When using a BVM, how often should you give rescue breaths? Conscious Choking—Adult and Child Adult: 1. To give back blows or abdominal thrusts, where would you position yourself? 2. What if the victim is obviously pregnant, known to be pregnant or too large to reach around? Child: 1. For a child, from whom would you obtain consent to give care? 2. To give back blows or abdominal thrusts, where would you position yourself? 3. When giving back blows or abdominal thrusts, what is one key item about the amount of force to use to keep in mind? Unconscious Choking—Adult and Child Adult: 1. If the first 2 rescue breaths do not make the chest clearly rise, what is your next step? 2. How far do you compress the chest of an adult? 3. What if the adult is obviously pregnant or known to be pregnant? 4. If you see the object, how do you remove it from the victim’s mouth? Child: 1. If the first 2 rescue breaths do not make the chest clearly rise, what is your next step? 2. How far do you compress the chest of a child? 3. If you see the object, how do you remove it from the child’s mouth? CPR—Adult, Child and Infant Adult: 1. How far do you compress the chest of an adult? 2. What if the adult is obviously pregnant or known to be pregnant? 3. What is the correct way to place your hands to give compressions for an adult? Child: 1. How far do you tilt the child’s head to open the airway? 2. How far do you compress the chest of a child? 3. What is the correct way to place your hands to give compressions for a child? Infant 1. How far do you compress the chest of an infant? 2. What is the correct way to place your hands to give compressions for an infant? Rate of CPR compressions 1. What is the rate of compressions for an adult, child and infant? Two-Rescuer CPR—Adult, Child and Infant Adult: 1. How far do you compress the chest of an adult? 2. What if the adult is obviously pregnant or known to be pregnant? 3. What is the ratio of compressions to breaths for an adult in two rescuer CPR? 4. The two rescuers should change positions regularly. When? Child: 1. How far do you tilt the child’s head to open the airway? 2. How far do you compress the chest of a child? 3. What is the ratio of compressions to breaths for a child in two rescuer CPR? 4. The two rescuers should change positions regularly. When? Infant: 1. What is the correct hand position for two rescuer CPR compressions on an infant? 2. What is the ratio of compressions to breaths for a infant in two rescuer CPR? AED—Adult and Child Adult: 1. Where do you attach the AED pads for an adult? Child: 1. Where do you attach the AED pads for a child? Initial Assessment: Child: 1. How far do you tilt the child’s head to open the airway? Infant: 1. How do you check an infant for consciousness? 2. How far do you tilt an infant’s head to open the airway? 3. How do you check an infant’s pulse? Adult: 1. When using a BVM, how often should you give rescue breaths? Child: 1. How far do you tilt the child’s head to open the airway? 2. When using a BVM, how often should you give rescue breaths? Infant: 1. How far do you tilt an infant’s head to open the airway? 2. When using a BVM, how often should you give rescue breaths? Adult: 1. To give back blows or abdominal thrusts, where would you position yourself? 2. What if the victim is obviously pregnant, known to be pregnant or too large to reach around? Child: 1. For a child, from whom would you obtain consent to give care? 2. To give back blows or abdominal thrusts, where would you position yourself? 3. When giving back blows or abdominal thrusts, what is one key item about the amount of force to use to keep in mind? Adult: 1. If the first 2 rescue breaths do not make the chest clearly rise, what is your next step? 2. How far do you compress the chest of an adult? About 1 1 /2 to 2 inches 3. What if the adult is obviously pregnant or known to be pregnant? 4. If you see the object, how do you remove it from the victim’s mouth? Child: 1. If the first 2 rescue breaths do not make the chest clearly rise, what is your next step? 2. How far do you compress the chest of a child? About 1 to 1 1 /2 inches 3. If you see the object, how do you remove it from the child’s mouth? CPR—Adult, Child and Infant Adult: 1. How far do you compress the chest of an adult? About 1 1 /2 to 2 inches 2. What if the adult is obviously pregnant or known to be pregnant? 3. What is the correct way to place your hands to give compressions for an adult? Child: 1. How far do you tilt the child’s head to open the airway? 2. How far do you compress the chest of a child? 3. What is the correct way to place your hands to give compressions for a child? Infant 1. How far do you compress the chest of an infant? 2. What is the correct way to place your hands to give compressions for an infant? Rate of CPR compressions 1. What is the rate of compressions for an adult, child and infant? Two-Rescuer CPR—Adult, Child and Infant 1. How far do you compress the chest of an adult? 2. What if the adult is obviously pregnant or known to be pregnant? 3. What is the ratio of compressions to breaths for an adult in two rescuer CPR? 4. The two rescuers should change positions regularly. When? Child: 1. How far do you tilt the child’s head to open the airway? 2. How far do you compress the chest of a child? 3. What is the ratio of compressions to breaths for a child in two rescuer CPR? 4. The two rescuers should change positions regularly. When? Infant: 1. What is the correct hand position for two rescuer CPR compressions on an infant? 2. What is the ratio of compressions to breaths for a infant in two rescuer CPR? AED—Adult and Child Adult: 1. Where do you attach the AED pads for an adult? Child: 1. Where do you attach the AED pads for a child?

* During the CPR, what is the percentage of heart efficiency as a pump?

* I heard that no matter if a person is unconscious that you should perform CPR. Is this true? When should you not perform CPR? | * What is the ratio of 2-person CPR? * How do I perform CPR on a person who has a trachea? Do I have to cover their mouth or just breath directly into the stoma? * When you are giving mouth to mouth are you actually breathing oxygen into the victim's lungs or are you trying to stimulate breathing by breathing carbon dioxide into their lungs? * When performing CPR, how do I know if its working? * If a person has had bypass surgery, and a situation occurs that they require CPR, are there any special considerations that need to be made? * What if the victim has a pulse, but is not breathing? * Is it easier to break an overweight persons ribs or a skinner persons ribs when performing cpr? * Can I kill someone if I do CPR incorrectly? * What if I crack a rib when I do CPR? * Will CPR always save a life? * What is the recovery position? * What should you do for a person who has been accidentally shocked by electricity? * I want to know what the current teachings are on helping a choking victim. I have heard conflicting information on back blows for an adult. Is it still recommended, or discouraged? * What if the victim vomits? * If someone has an asthma attack and collapses, what should a person do? Will CPR help? * What are some of the causes of CPR being used for in infants and children? * In regards to administering the Heimlich Maneuver to a victim while they are lying down. Should the head be facing up, as when administering CPR (in order to clear the airway), or to the side? * What if the victim is wearing dentures? * Can I get AIDS from doing CPR? * Can I get sued if I perform CPR? * Does the Good Samaritan law protect me? * What are agonal respirations? * In cardiopulmonary arrest occurring outside of a hospital what are statistics regarding successful uncomplicated recovery? Also in this situation how many patients are successfully resuscitated but are then in a vegetative state? * Can CPR be performed on dogs? * What if I'm not sure whether I feel a pulse in the neck of the victim? * If a person moves when I do CPR should I stop? * When should I stop CPR? * What chance does the person (on whom I perform CPR) have of surviving? * What should I do if I'm alone and I do not know CPR? * If a pregnant women chokes should I do the Heimlich Maneuver or can it harm the baby? * What is the reason calling 911 occurs after 1 minute of CPR for infants and children whereas for adults, the call is made immediately? * If successful CPR is dependent on a defibrillator arriving, are there any portable defibrillators available? * In a trekking guidebook I own it states that if there has been a trauma fall and the victim has no pulse, then CPR is futile, is this true? * Is it true that if a victim "regains" a pulse after doing CPR he/she has probably had a pulse all along?

1. How far down should the sternum be depressed while performing a chest compression on a child? | 2. How far down should the sternum be depressed while performing a chest compression on an adult? 3. How far down should the sternum be depressed while performing a chest compression on an Infant? 4. What is the AHA age range for Adult procedures? 5. What is the AHA Basic Life Support age range for Infant procedures? 6. What is the AHA age range for child procedures? 7. When rescue breathing for an Infant with a pulse, give one ventilation every? 8. When rescue breathing for an Adult with a pulse, give one ventilation every? 9. When rescue breathing for a Child with a pulse, give one ventilation every? 10. How would you describe hand placement on the chest to perform a compression on an Infant? 11. How would you describe hand placement on the chest to perform a compression on an Adult? 12. How would you describe hand placement on the chest to perform a compression on a Child? 13. What is the rate of chest compressions for an Adult in one minute? 14. What is the rate of chest compressions for a Child in one minute? 15. What is the rate of chest compressions for an Infant in one minute? 16. When do you get help for an unresponsive Adult victim? 17. When do you get help for an unresponsive Child or Infant victim, when you are alone? 18. What is the step just before you ventilate in the CAB's? 19. Which of the following choices are the most modifiable risk factors for stroke and heart attack? 20. What is the most common cardiac rhythm that an adult is most likely to experience in early cardiac arrest? 21. How old should an adult victim be to have an automated external defibrillator (AED) placed on them? 22. What is the ratio of compressions to ventilations when performing one rescuer CPR on an Adult? 23. What is the ratio of compressions to ventilations when performing two rescuer CPR on an Adult? 24. What is the ratio of compressions to ventilations when performing one rescuer CPR on an Infant? 25. What is the ratio of compressions to ventilations when performing one rescuer CPR on an Child? 26. What is the ratio of compressions to ventilations when performing two rescuer CPR on a 3 week old according to the AHA Basic Life Support Healthcare Provider Standard course? 27. Pulse check location for a Child? 28. When do you reassess a victim once CPR is started? 29. A bag-valve-mask device is preferred to ventilate a non-breathing victim over a mouth-to mask device. 30. A mouth-to-mask device delivers greater tidal volume of air compared to a bag-valve-mask. 31. Why is it not advisable to do a blind finger sweep on unconscious choking infants and children? 32. When do you get help for a conscious choking adult, if you are alone? 33. When delivering ventilations to a non-breathing victim using room air only, each ventilation should be delivered over? 34. When providing a chest compression your hands should allow the chest to reach full recoil. 35. When evaluating a conscious choking persons airway for blockage, which of the following questions would be the least preferred for the rescuer to ask? 36. List three reasons when chest thrusts would be performed on a conscious choking victim instead of abdominal thrusts. 37. What are the three most common reasons that lead to gastric distention (air in the stomach)? 38. Approximately 75% of heart attack victims experience chest pain. 39. When using a bag-valve-mask as a single rescuer how is the mask held to the face? 40. What is the preferred method to open the airway of a non-trauma victim? 41. What is the AHA Chain of Survival when treating an Adult cardiac arrest? 42. The goal to save an Adult cardiac arrest is? 43. When is compression only CPR recommended with no ventilations in this country? 44. How long should the initial pulse check last? 45. What is the name given to the position of placing the victim on their side?

Q. What is CPR?

| Q. Who regulates CPR? Q. How often do the CPR guidelines change? Q. Does the change from ABC to CAB CPR apply to everyone? Q. Why did the AHA guidelines change so significantly? Q. What are the main characteristics of high quality chest compressions? Q. Why is continuous chest compression CPR often just as effective as traditional CPR? Q. Why not do away with rescue breathing completely? Q. If I learnt the old CPR do I need to stop administering CPR until I become certified in the new CAB way? Q. If I have recently passed my CPR certification, do I have to recertify in accordance with the new AHA guidelines? Q. Can I kill someone by giving CPR the wrong way? Q. How often does CPR save someone’s life? Q. What are the Good Samaritan Laws and will they protect me from being sued? Q. Can CPR be used on animals? Q. Ok I am convinced! Where should I take my CPR classes?

What is Hands-OnlyTM CPR?

|

Do you have questions on how to do CPR? | If someone collapses near you do you know what to do?

1. Are you __________ Certified? | 2. How long is your course(s)? Do I have to finish it all in one sitting? 3. How are your instructors trained? 4. How long will it take to receive my wallet certification card? 5. What if I don't pass the quiz at the end of the course? 6. Does your course require an outside hands-on test? 7. How much do your courses cost? 8. What happens once I've taken the __________' online course? 9. How long are your courses good for? 10. Is your certification accepted by my state? 11. What are my choices for a method of payment? 12. How do I print my certification once I have passed? 13. What is an AED?

CPR information | STANDARD CPR FOR ADULTS - CPR in three simple steps HANDS-ONLY CPR FOR ADULTS - CPR in two simple steps CPR FOR CHILDREN - CPR in three steps for small children CPR FOR INFANTS - CPR for infants in five simple steps STANDARD CPR POCKET GUIDE - Printable CPR instructions HANDS-ONLY CPR POCKET GUIDE - Printable CPR instructions CPR FOR CATS & DOGS - CPR instructions for your family pet STANDARD CPR FOR ADULTS VIDEO - Standard CPR techniques for adults HANDS-ONLY CPR FOR ADULTS VIDEO - Hands-only CPR techniques for adults CPR FOR CHILDREN VIDEO - CPR techniques for children CPR FOR INFANTS VIDEO - CPR techniques for infants CHOKING ADULT VIDEO - First aid for a choking conscious adult CHOKING CHILD VIDEO - First aid for a choking conscious child CHOKING INFANT VIDEO - First aid for a choking conscious infant FREE iPHONE APP - Take the videos wherever you go free. FREE ANDROID APP - Free training app for Android equipped phones. CONSCIOUS ADULTS - First aid for a conscious adult CONSCIOUS CHILD - First aid for a choking child CONSCIOUS INFANTS - First aid for a choking infant CPR FAQ - Have a question about CPR? Check here first CPR FACTS - Facts and general information about CPR CPR LINKS - Links to other great CPR resources CPR QUIZ - Think you're an expert? Take our quiz and test yourself CPR HISTORY - Interested in learning about the history of CPR? |

| Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support |

| Prolonged Life Support (PLS) |

|

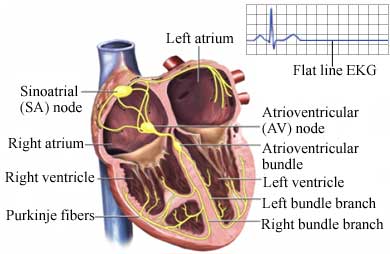

What is cardiac arrest? Cardiac arrest is the sudden, abrupt loss of heart function. The victim may or may not have diagnosed heart disease. It's also called sudden cardiac arrest or unexpected cardiac arrest. Sudden death (also called sudden cardiac death) occurs within minutes after symptoms appear. What causes cardiac arrest? The most common underlying reason for patients to die suddenly from cardiac arrest is coronary heart disease. Most cardiac arrests that lead to sudden death occur when the electrical impulses in the diseased heart become rapid (ventricular tachycardia) or chaotic (ventricular fibrillation) or both. This irregular heart rhythm (arrhythmia) causes the heart to suddenly stop beating. Some cardiac arrests are due to extreme slowing of the heart. This is called bradycardia. Other factors besides heart disease and heart attack can cause cardiac arrest. They include respiratory arrest, electrocution, drowning, choking and trauma. Cardiac arrest can also occur without any known cause. Differential Diagnosis Why did arrest occur? Are there any other factors? Can we reverse the cause(s)? 7 H's and 6 T's: pnemonic for mechanisms * hypoxia * hypovolemia * hyperkalemia * hypokalemia * hypoglycemia * hypothermia * hydrogen ions (acidosis) * thrombosis (MI) * tension pneumothorax * tamponade * toxins/therapeutics * thromboembolism * trauma Heart conditions that can lead to sudden cardiac arrest More often, a life-threatening arrhythmia develops in a person with a pre-existing heart condition, such as: * Coronary artery disease. Most cases of sudden cardiac arrest occur in people who have coronary artery disease. In coronary artery disease, your arteries become clogged with cholesterol and other deposits, reducing blood flow to your heart. This can make it harder for your heart to conduct electrical impulses smoothly. * Heart attack. If a heart attack occurs, often as a result of severe coronary artery disease, it can trigger ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac arrest. In addition, a heart attack can leave behind areas of scar tissue. Electrical short circuits around the scar tissue can lead to abnormalities in your heart rhythm. * Enlarged heart (cardiomyopathy). This occurs primarily when your heart's muscular walls stretch and enlarge or thicken. In both cases, your heart's muscle is abnormal, a condition that often leads to heart tissue damage and potential arrhythmias. * Valvular heart disease. Leaking or narrowing of your heart valves can lead to stretching or thickening of your heart muscle, or both. When the chambers become enlarged or weakened because of stress caused by a tight or leaking valve, there's an increased risk of developing arrhythmia. * Congenital heart disease. When sudden cardiac arrest occurs in children or adolescents, it may be due to a heart condition that was present at birth (congenital heart disease). Even adults who've had corrective surgery for a congenital heart defect still have a higher risk of sudden cardiac arrest. * Electrical problems in the heart. In some people, the problem is in the heart's electrical system itself, instead of a problem with the heart muscle or valves. These are called primary heart rhythm abnormalities and include conditions such as Brugada's syndrome and long QT syndrome. Can cardiac arrest be reversed? Brain death and permanent death start to occur in just 4 to 6 minutes after someone experiences cardiac arrest. Cardiac arrest can be reversed if it's treated within a few minutes with an electric shock to the heart to restore a normal heartbeat. This process is called defibrillation. A victim's chances of survival are reduced by 7 to 10 percent with every minute that passes without CPR and defibrillation. Few attempts at resuscitation succeed after 10 minutes. How many people survive cardiac arrest? No statistics are available for the exact number of cardiac arrests that occur each year. It's estimated that more than 95 percent of cardiac arrest victims die before reaching the hospital. In cities where defibrillation is provided within 5 to 7 minutes, the survival rate from sudden cardiac arrest is as high as 30–45 percent. What can be done to increase the survival rate? Early CPR and rapid defibrillation combined with early advanced care can result in high long-term survival rates for witnessed cardiac arrest. For instance, in June 1999, automated external defibrillators (AEDs) were mounted 1 minute apart in plain view at Chicago's O'Hare and Midway airports. In the first 10 months, 14 cardiac arrests occurred, with 12 of the 14 victims in ventricular fibrillation. Nine of the 14 victims (64 percent) were revived with an AED and had no brain damage. If bystander CPR was initiated more consistently, if AEDs were more widely available, and if every community could achieve a 20 percent cardiac arrest survival rate, an estimated 40,000 more lives could be saved each year. Death from sudden cardiac arrest is not inevitable. If more people react quickly by calling 9-1-1 and performing CPR, more lives can be saved. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) What is CPR? Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a combination of rescue breathing and chest compressions delivered to victims thought to be in cardiac arrest. When cardiac arrest occurs, the heart stops pumping blood. CPR can support a small amount of blood flow to the heart and brain to “buy time” until normal heart function is restored. Cardiac arrest is often caused by an abnormal heart rhythm called ventricular fibrillation (VF). When VF develops, the heart quivers and doesn't pump blood. The victim in VF cardiac arrest needs CPR and delivery of a shock to the heart, called defibrillation. Defibrillation eliminates the abnormal VF heart rhythm and allows the normal rhythm to resume. Defibrillation is not effective for all forms of cardiac arrest but it is effective to treat VF, the most common cause of sudden cardiac arrest. Cardiac arrest refers to the loss of heart function. In many cases, it is an expected outcome to a serious illness. Cardiac arrest often results in death. * Sudden cardiac arrest refers to the heart unexpectedly stopping activity due to a potentially reversible cause. Brain death occurs within a few minutes if the situation is not reversed. o Sudden cardiac arrest may be caused by many different conditions. It does not necessarily mean that the person has had a heart attack. * Sudden cardiac death refers to an unexpected, heart-related death within 1 hour from the start of symptoms. Electrical System of the Heart  Causes Causes of cardiac arrest include: * Ventricular fibrillation —a rapid, irregular heart rhythm preventing any circulation of blood (most common cause of sudden cardiac arrest) * Ventricular tachycardia —a rapid but regular heart rhythm that, if sustained, may turn into ventricular fibrillation * Dramatic slowing of heart rate due to failure of its pacemaker or severe heart block (interference with electrical conduction) * Respiratory arrest * Choking or drowning * Electrocution * Hypothermia * Sudden loss of blood pressure * Unknown causes Risk Factors A risk factor is something that increases your chance of getting a disease or condition. Risk factors for cardiac arrest include: * Coronary artery disease * Heart attack * Cardiomyopathy * Enlarged heart * Congenital heart disease * Improperly functioning heart valves * Conditions affecting the heart's electrical system * Severe meta2bolic imbalances * Adverse drug effects, such as from drugs to treat abnormal heart rhythms * Lung conditions * Trauma to the chest * Extensive blood loss * Excessive overexertion in people with heart disorders * Use of illicit substances (eg, cocaine ) Symptoms Symptoms include: * Loss of consciousness * No breathing * No pulse Prior to cardiac arrest, some patients report the following symptoms or warning signs in the weeks before the event: * Chest pain * Weakness * Pounding in the chest * Feeling faint Diagnosis The first person to respond to a cardiac arrest should check if the person is responsive. If the person does not respond, call 911 right away or have someone else call. If there is an automated external defibrillator (AED) available, you or someone else should get it and follow the steps on the machine. After calling 911, CPR will be started if the person is not breathing normally. If no AED is available or while you are waiting for it, begin doing CPR by giving chest compressions. Push in the chest at least two inches at a fast rate of at least 100 compressions per minute. If you are trained in CPR, after 30 compressions, open the person's airway and give two rescue breaths. Then, continue with the chest compressions. If you feel more comfortable, you can give the compressions without the breaths until the ambulance arrives. Treatment Prompt treatment improves the chance of survival. The four steps in the cardiac chain of survival are: Call 911 Immediately call for emergency medical support. Call 911 as soon as you notice cardiac warning signs or suspect a cardiac arrest has occurred. Defibrillation Defibrillation sends an electrical shock through the chest. The surge of electricity aims to stop the ineffective, irregular heart rhythm. This may allow the heart to resume a more normal electrical pattern. AEDs check the heart rhythm before instructing the rescuer to give the shock. Start CPR CPR helps keep blood and oxygen flowing to the heart and brain until other treatment can be given. The heart and brain are very susceptible to low oxygen levels. Permanent damage can occur, even with successful resuscitation. Advanced Medical Care Paramedics at the scene and doctors at the hospital provide essential medical care and intensive monitoring. They will give drugs, insert a tube to maintain an open airway, and manage emergency care. Epinephrine is often given early to make the heart more receptive to electrical impulses and improve blood flow to the heart and brain. The patient will receive oxygen. Even if an effective heart rhythm is restored, low oxygen levels may cause serious complications, including damage to the heart, brain, and other vital organs. The emergency medical personnel may perform an electrocardiogram (ECG, EKG)—a test that records the heart's activity by measuring electrical currents through the heart muscle. Doctors will attempt to find and correct the underlying cause of the cardiac arrest. At the hospital, the doctor will ask about symptoms prior to the collapse and the patient's medical and drug history. If the patient survives, the doctor will: * Assess the electrocardiogram. * Perform a physical exam. * Confirm a cardiac arrest has occurred. * Look for the cause. * Evaluate the effects of pre-hospital care. * Order additional blood and diagnostic tests to help determine the cause of the arrest. A telemetry machine will continually monitor the heart's electrical activity. Prevention Become aware of heart disease warning signs and promptly seek treatment for any that develop. If you do not have a heart condition, follow the rules of primary prevention of heart disease. If you have a heart condition or may be at high risk for one, ask your doctor about how to reduce your risk of sudden cardiac arrest. You might be a right candidate for certain medications that prevent heart arrhythmias or implantation of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) device. Also, if you are known to be at high risk, you may consider purchasing an automatic external defibrillator (AED) for home use. Discuss it with your doctor. http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=4481 http://www.aurorahealthcare.org/yourhealth/healthgate/getcontent.asp?URLhealthgate=11981.html http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/cardiology/cardiovascular%2Demergencies/ |