Jet engines

Last updated: April 7, 2010.

Jet engines have put rockets into space

and

powered boats and automobiles to world speed records, but they are more

familiar as the

engines on airplanes such as Concorde and the Jumbo Jet.

Unlike

internal combustion engines in automobiles and trucks, which convert an

up-and-down movement of pistons into rotary movement in a

crankshaft, jet engines produce power by sucking in air at the front

and blasting out hot exhaust gases at the back. Let's take a closer

look at how they work!

Photo: A jet engine taken apart during testing.

You can clearly see the giant fan at the front. This spins around to suck air into the

engine as the plane flies through the sky. Picture by Ian Schoeneberg courtesy of

US

Navy.

What is a jet engine?

A jet engine is a machine for turning fuel into thrust (forward

motion). The thrust is produced by action and

reaction—a

piece of physics also known as Newton's third law of motion. The force

(action)

of the exhaust gases pushing backward produces an equal and opposite

force (reaction) called thrust that powers the vehicle forward. Exactly

the same principle pushes a skateboard forward when you kick backward

with your foot. In a jet engine, it's the exhaust gas that provides the

"kick". Let's have a look inside the engine...

How a jet engine works

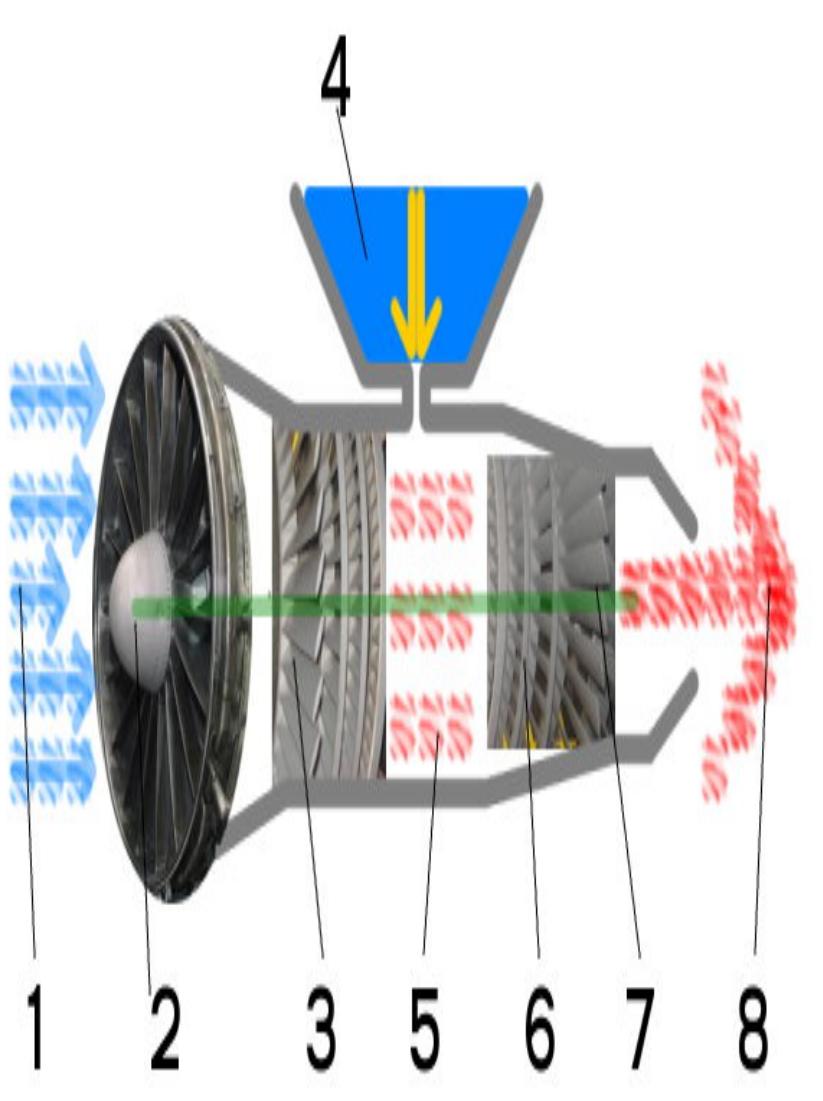

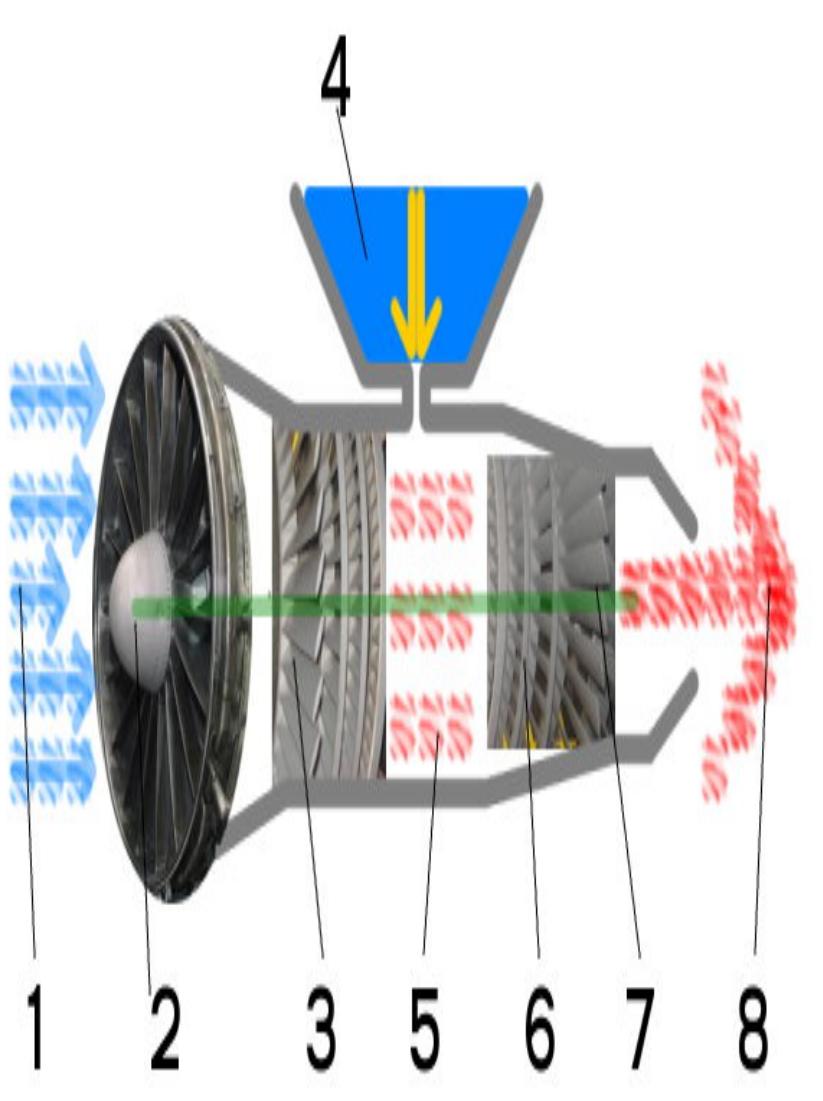

This simplified diagram shows you the process through which a jet engine converts the energy in fuel into

kinetic energy that makes a plane soar through the air:

- For a jet going slower than the speed of sound,

the engine is moving through the air at about 1000 km/h (600 mph).

We can think of the engine as being stationary and the cold air moving

toward it at this speed.

- A fan at the front sucks the cold air

into the engine.

- A second fan called a compressor

squeezes the air

(increases its pressure) by about eight times. This slows the air down

by about 60 percent and it's speed is now about 400 km/h (240 mph).

- Kerosene (liquid fuel) is squirted into the engine from a fuel

tank in the plane's wing.

- In the combustion chamber, just behind

the compressor,

the kerosene mixes with the compressed air and burns fiercely, giving

off hot exhaust gases. The burning mixture reaches a temperature of

around 900°C (1650°F).

- The exhaust gases rush past a set of turbine blades,

spinning them like a windmill.

- The turbine blades are connected to a long axle

(represented by the green line) that runs the length of

the engine. The compressor and the fan are also connected to this axle.

So, as the turbine blades spin, they also turn the compressor and the

fan.

- The hot exhaust gases exit the engine through a tapering exhaust

nozzle. The tapering design helps to accelerate the gases to a

speed of over 2100 km/h (1300 mph).

So the hot air leaving the engine at the back is travelling over

twice the speed of the cold air entering it at the front—and

that's what powers the plane.

Military jets often have an after

burner that squirts fuel into the exhaust jet to produce extra

thrust. The backward-moving exhaust gases power the jet forward. Because

the plane is much bigger and heavier than the exhaust gases it

produces, the exhaust gases have to zoom backward much faster than the

plane's own speed.

Photo: Top artwork: This composite artwork uses part of the top photo on this page, taken

by Ian Schoeneberg and courtesy of US Navy, combined with a photo of a turbine exhibit at Think Tank, the science museum in Birmingham, England, which we

took ourselves.

Photo: Bottom photo: Massive thrust! A Pratt and Whitney F119

jet aircraft engine creates 156,000 newtons (35,000 pounds) of thrust

during this US Airforce test in 2002. Picture by Albert Bosco courtesy of US

Airforce.

Types of jet engines

British engineer Sir Frank Whittle (1907–1996) invented the jet

engine in 1930, but the design has evolved quite a bit since then.

Now there are several different types of jet engines, each working in

a slightly different way.

Turbojet

Whittle's original design was called a turbojet and it's still widely used in

airplanes today. Turbojets are basic, general-purpose jet engines.

The engine we've explained and illustrated up above is an example.

Read more about turbojets on Wikipedia.

Photo: Early Turbojet engines on a Boeing B-52A Stratofortress plane, pictured in 1954.

The B-52A had eight Pratt and Whitney J-57 turbojets, each of which could produce about 10,000 pounds of thrust.

Picture courtesy of US Air Force.

|

|

Turboprop

Turboprop engines have a propeller at the front and are popular in smaller, more economical aircraft and helicopters. The propeller is

driven by a jet engine mounted directly behind it.

Read more about turboprops on Wikipedia.

Photo: A turboprop engine uses a jet engine to power a propeller. Photo by Eduardo Zaragoza courtesy of US Navy.

|

|

Turbofan

Turbofan engines are much quieter than turbojets and are typically used in large airliners. A turbofan

engine has a large fan that sucks in air at the front.

Some of the air is blown into the compressor; the rest is blown around

the outside of the combustion chamber and straight out of the back.

This "bypass" arrangement cools the engine and makes it much quieter.

It also produces much more thrust at both takeoff and landing.

Read more about turbofans on Wikipedia.

Photo: A turbofan engine produces more thrust using an inner fan and an outer bypass (the smaller ring you can see between the inner fan and the outer case). Each one of these engines produces 43,000 pounds of thrust (almost 4.5 times more than the Stratofortress engines up above)! Photo by Lance Cheung courtesy of US Air Force.

|

|

Ramjets and scramjets

Ramjets are simple and compact jet engines—little more than gas-burning pipes, typically used to power rockets and guided missiles. Scramjets are supersonic ramjets (ones in which air travels through the engine faster than the speed of sound).

Read more about ramjets on Wikipedia.

Read more about scramjets from NASA.

Photo: A Pegasus ramjet/scramjet engine developed for space planes in 1999.

Photo by courtesy of NASA Dryden Flight Research Center (NASA-DFRC).

|

|

http://www.explainthatstuff.com/jetengine.html

|